|

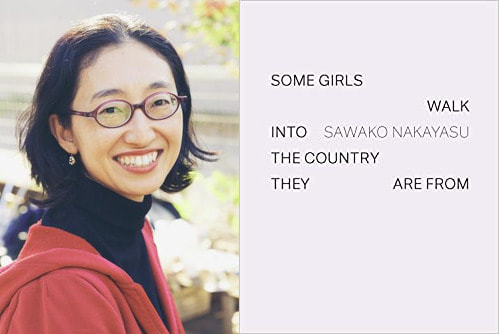

I want to write of origin. But how does one adequately speak about something so monumental? So subjective & unique? We all have our own beginnings, our own associations with this word, origin. Some of us might attribute our creation linearly, or by our birth in this life. Some of us might see it as when our souls first arrived, lifetimes & universes ago. No matter your take on the subject, no matter your personal associations, I think we can all agree that our beginning often sways the paths we take, how we form, what stays with us as we move into the world. But does it need to? Does our origin need to dictate the self? There are two major etymological meanings of the word origin. The first is as described above. From the Latin originem meaning, "a rise, commencement, beginning, source; descent, lineage, birth.” However, from the Sanskrit iyarti, it means "to set in motion, move." To begin/to move. To birth/to reimagine. It is in the tension between these two meanings of origin that we find today’s Full Capricorn Moon in Cancer. As of the Summer Solstice on June 20th, we are in Cancer season. Cancer is cardinal water, and can very easily be interpreted as a mothering feminine energy. The crab’s deep waters can at once soothe and unnerve. Can mimic the motions of the womb and the unnerving overwhelm of swimming alone in the ocean. On the other hand, Capricorn, our steadfast cardinal earth sign, radiates the fathering masculine. It can tenderly guide or harshly discipline. It can ground us in inspiration and responsibility, or crush all creativity under a rockslide of micromanagement. As I’ve mentioned in other offerings, every sign has a shadow. And none of these energies operate in a binary. The described manifestations of masculinity and femininity can happen simultaneously, cyclically, etc. Capricorn and Cancer don’t need to represent the heteronormative mother/father duality or family, either. But what they can represent is the tension and collaboration between mothering and fathering that we hold within ourselves. I also want to say that many of us don’t embrace, or maybe even know, all or parts of our origin story. Sometimes working with our beginnings, or even our child selves, can be harmful or painful. I’ve said it before, and I’ll echo it again here: please don’t go anywhere you can’t come back from. What I do believe this Full Capricorn Moon in Cancer is gifting us is a moment to gain clarity, and perhaps even acceptance, around our origin. Not so that we can remain in the past, but so we can channel it towards the other embedded energy within origin: to set something in motion. What are ways we can re-learn or reimagine our inner parenting in order to achieve fulfillment? What parts of your origin, your lineage, need to be left behind? What can be brought with you? What definitions of mother/father or masculine/feminine need to be broken or expanded within you so that you feel fully held by your inner parent? How can our origin become both a space for reprieve and a launch pad for passion? Tarot Reading | 7 of Cups Reversed This card in this position speaks to the true power and motion that can arise when the Cancer/Capricorn energies come together in harmony. Upright, this card is about being stuck in fantasies, dreams, or emotions without a course of action to make them a reality. Reversed, however, we find our path out of fantasyland, not by shrugging dreams off as immaterial, but by embracing them as possible. By embracing the authenticity and ancient wisdom of our emotions/fantasies (Cancer) alongside our action-oriented, grounded self (Capricorn), there’s no stopping us. The actions we set in motion find footing internally and externally. And by doing so, we learn more about our true origins. As Marie White, creator of Mary El Tarot, writes of the wolf shown on this card: The forest is reality. It is dense and alive, growing and changing. There are many ways through it. There is a well-worn path, tended to and passed down from our ancestors and society. We can take this path with relative ease; or, we can create our own path through the forest, the one that is best to reach our highest potential as an individual human being. This wolf is the one you meet when you go off the path. He is your own animal self. Wild, passionate, and dangerous, he isn’t tamed and ‘well bred,’ he is majestic and natural. It is such a difficulty for people to balance the beastly and the civilized nature in themselves, but done, it can be channeled into greatness. Accepting our watery, moon-soaked, wild origins; accepting the grounding of experience, the one that can only be gained by purposefully leaving aspects behind us--this is what allows us to clearly see, maybe even for the first time, not just a path, but our path. Bibliomancy | “Girl in her Dreamings and Girl in her Hair” | pg. 38 from Some girls walk into the country they are from by Sawako NakayasuThe mistake is in both belief and memory. At that Girl H lies down flat she is like that. On the bed, she sinks in. In the street, she gets run over. Over a body—body of water—her hair spreads, largest and smallest as a convergent point burned by the unbearable light. Her dreamings do not fracture, they leach slowly into the water, the street, the sheets. Even more slowly, they are welcomed or rejected based on their color. When she catches on to what is happening, she takes to hiding her dreamings, in her hair. Her hair goes long, longer, all the better to hide more and more believings.

0 Comments

Shawnie Hamer (SH): Alright, let's jump in! Where did the idea for Have Snakes, Need Birds come from? This project took 7 years, right? What iterations did it take over that time? How were you able to decide the paths it would take? Travis Klempan (TK): Instead of having an idea for a story and then building it out, I had a single line that grew into a story. Eight years ago I was dating someone who said (after seeing a clip of Atticus Finch in the movie adaptation of To Kill a Mockingbird claim that all mockingbirds do is “sing their hearts out”) “Harper Lee is full of shit.” She told me that, where she grew up, mockingbirds were the hooligans of the bird world, tearing into dumpsters and throwing garbage around. For some reason, that image and that line stuck with me. (For the record, I don’t think she actually thought Harper Lee was full of shit): the image of mockingbirds feasting on a dumpster, probably somewhere in the American South. I started turning that line over and over in my head and finally saw someone watching the birds, perhaps throwing pebbles at the dumpster to set them to flight. I asked myself why he’d be doing that, and the answer was “Wasting time.” Who waits around more than young soldiers waiting to go off to war . . . and that was the kernel around which the rest of the story grew. For a year or so before that summer, I’d tried writing other stuff, off and on, but nothing felt big enough or promising enough to explore further. Who was this guy, I wondered. What was John’s role in the world? Who were the people around him? I started seeing things that fit together into a story. I attended Riot Fest that fall and saw this young man—named John Carter at the time—at a similarly weird music festival. His name changed to John Mackenzie based on a song I heard on the radio; other characters came and went, consolidated or split apart on the page; and the two malicious forces in the story came from misheard words. The structure changed, but not significantly. It was always going to take about a year or little less on the page. Some of the dynamics changed pretty substantially, though. I tried it as first-person and it never seemed to work, especially as I met these other characters and realized I needed to get in their heads to really tell the story. I changed some names to avoid confusion (and in one case to introduce it, intentionally) for the reader, and excised entire substories and secondary narratives. There’s still a lot of that in there, those sorts of side quests (to borrow a phrase) that I think not only help illuminate and demonstrate character but can also just be diversionary and fun. In response to receiving these interview questions I went back and looked at a lot of my saved material. I don’t know if it’s my natural inclination or being so enamored of the notion of the archive from my time at Naropa, but I tend to keep a lot of stuff related to my writing . . . not just notes (I have entire spreadsheets with dates and calendars to keep things straight, like what night a full moon would have occurred in 2007, or when was sunset in Baghdad in December) but also drafts, at least when they make significant changes. Some of the older drafts showed John as brutally cynical, very bitter, and I realized at one point I didn’t want to show another disgruntled soldier in a stereotypical war narrative. I think that was the biggest change, breaking away from the typical combat story of young man going off to war. Introducing (or uncovering, revealing, excavating) the supernatural elements really opened up the book. I don’t think I went so far as to assign blame for violence on the two malevolent forces (Moonlit Samuel and taliment), but I kept circling back to this idea of stories and storytelling, that speaking stories can bring them into existence, and that kind of magic has consequences. So in some ways maybe it’s ultimately a book about stories. SH: What was your writing process for this book? Tell us about your rituals. TK: I loved writing the lion’s share of this book in public spaces. I think there was an element of accountability, even if the people in the coffee shops didn’t know what I was doing. I also wrote or rewrote sections while on trains and planes, and during visits to see family in other states. I also listened to music almost constantly while writing. Often it would be background instrumental or atmospheric stuff—lots of classical music—but I kept a playlist of songs that connected either directly or indirectly to the action and the characters: who was listening to what, and when, or music that amplified the feeling of a scene. As an example, I must have played “Host of Seraphim” by Dead Can Dance a couple hundred times, it felt like, to get into the proper mood for a couple of key scenes. Editing and revising was a whole other story. I think I had the major bones of the book within a year or so, but fleshing that out, getting it to work right, I went through lots of major changes, and each time something like the POV or the tense or plot would change, then I’d have to go back through and make sure everything still connected. Even after having the book published, I think I’m going to hang on to all these old documents and drafts . . . it’s kind of fun to go digging through the discarded heaps of my personal archive! SH: What were you most afraid of and/or excited about in writing this book? TK: A lot of things were on my mind as I wrote. I wanted to get a lot of the technical aspects right, or as close as I could without inundating the reader with jargon and minutiae, so that it still rang true to people who were in the military generally and in the Army specifically. I didn’t want to glorify war by any means, but I did want to convey the exhilaration that comes from high-intensity situations (without specifically leading the reader down one path to a conclusion or another). I also wanted it to appeal to as broad an audience as possible. I think a lot of military fiction can be esoteric or inscrutable to civilian audiences, and sometimes intentionally so, and if the book couldn’t connect with readers outside the military or veteran world, then that would have been a failure, in my mind. (Luckily I’ve had positive reactions from both sides of the bridge.) What was probably the most difficult, though, in terms of wanting to get something as true on the page as I could, was writing characters whose identities I did not share—specifically, a lot of the soldiers are not straight white men, and there are a few women in this book who are critical to the story. I wanted to make sure none of them were caricatures, which is where I think my focus on dialogue helped. How we speak is often a reflection of how we think (even when there’s a disconnect between the two), and so I paid attention to how people spoke, not just in terms of diction or lexicon, but the cadences, the intentions, and the tenor of how people spoke, and how they spoke differently to different people. This was at least an entryway into portraying as authentically as possible people beyond what some might consider the stereotypical American soldier. Some of those characters were my favorite people in the book, so what was difficult became exciting. SH: If you could impart one piece of advice to our collective members writing a novel, what would it be? TK: Have at it. Take chances and risk failure. I sent out a lot of my chapters as short stories, whether to small presses or journals or as writing samples, and the feedback I got was formative and helpful. A lot of it was revealing, though, that the story as a whole was still under-developed. Take a section and rework it by changing something major, something like POV or tense or perspective. Write a flashback, write an action scene, strip it down to dialogue, take out all the dialogue. I have a whole set of background knowledge of the story, including things that never appear on the page, that helps inform and guide what gets written. Show it off and share it. I sent other pieces and even the whole thing to some mentors and colleagues and again, their responses helped shape the final product. I read it aloud to my girlfriend (now wife) . . . even if you don’t read it aloud to someone, try reading the whole thing aloud. That’s a lot of little pieces of advice I guess, so the big one is: take risks with your writing and your writing process. SH: What do you know about the publishing world/process now that you didn’t know before? TK: There are multiple paths to getting a book out into the world, so the definition of publishing seems to be broader than what is now called “traditional publishing.” I queried for years—agents who said they worked with veterans, small presses accepting unsolicited manuscripts, contests and universities—and got some really nice feedback, beyond the standard form rejection, most often something like “The writing is good and the story sounds interesting, we’re just not the right agent/press/person for it.” I would go through phases of querying like mad and then getting disappointed until something prompted me to get going again. In the last (and obviously successful) round, I found a place that bills itself as a “hybrid publisher,” which seems like a step up from self-publishing (in terms of streamlining a lot of the services) but a step below the traditional route (in terms of payments, contracts, agents, that kind of stuff). One thing I appreciated going with the hybrid was my level of control over the content and final product. I’ve heard that traditional publishing can change a lot of the pieces, including the title (and I’m glad I got to keep my title—I love it!), so was happy that I got to be as involved as I was. The cover design also turned out great, through a combination of a collaborative process and an online poll. I think what I’m getting at is: determine what your goal in getting your book into the world is. If it’s to have something you can hold onto or put on a shelf or in a bag, there are lots of options, but you have to be clear about what your choice offers and what it doesn’t. Marketing and promotion is almost entirely on me (as it is on anyone who self-publishes, too), so my sales are never going to be through the roof. Creative control never really got out of my hands, but a lot of the technical stuff like formatting and cover wraps was handled by professionals. Sign up for Travis' upcoming July workshop |

Authorcollective.aporia Archives

May 2023

Categories

All

© 2019-2021 collective.aporia

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed